Recount: Caught at daggers drawn in an attack, an Israeli-trained military against armed to the teeth separatist fighters

A bloodbath caused by reckless reactions to a peaceful strike started by lawyers and teachers in 2016, the Cameroon Anglophone crisis has claimed more than 2,000 lives, at least 200 villages burnt down, several people arrested and over 500,000 people rendered homeless.

Now a war zone with daily gun battles and guerilla attacks, the Anglophone regions of Cameroon have an increasing record of extrajudicial killings, arbitrary and unlawful detention, torture, imprisonment and spiraled accounts of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights on civilians, activists and Journalists.

The narrative – Cameroonian journalist and political blogger Arrey Bate chronicles the hostilities and killings in an investigative mission to the war-infested Anglophone regions. He shares an experience in his journey through military and separatist camps with records of brutal guerrilla attacks and summary executions.

Prologue

Placed on the Gulf of Guinea, Cameroon is a central African country made up of 10 regions. 8 of these regions are French speaking and 2 are English speaking. Cameroon is Africa’s only bilingual country and second in the world alongside Canada.

We can trace English and French languages to the colonial era in 1922 under Britain and France as trust territories of the League Of Nations.

France ruled French Cameroun, present 8 French-speaking regions (francophone regions) and Britain ruled Southern Cameroons, present 2 English-speaking regions (Anglophone regions).

In 1960, the French colonized territory gained independence and assumed the name ‘The Republic of Cameroon’ (French: La Republique Du Cameroun) under President Ahmadou Ahidjo. In 1961, the former British Southern Cameroons also gained independence but voted to join The Republic of Cameroon.

As a result, both territories met at the Foumban conference of July 1961 to draft a constitution and set living terms between British Southern Cameroons and The Republic of Cameroon.

The conference birthed the ‘Federal Republic of Cameroon’ under president Ahmadou Ahidjo.

But in 1972, Ahidjo abandoned federation and renamed the territory the United Republic of Cameroon. Southern Cameroons lost its autonomous status and became the Northwest region and Southwest region.

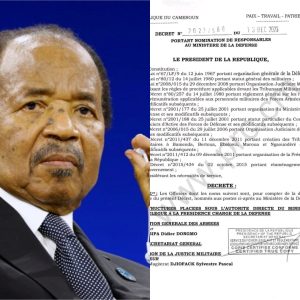

Paul Biya became president of Cameroon on November 6, 1982 following Ahidjo’s resignation. Two years later, he revised the constitution and changed the country’s name from the ‘United Republic of Cameroon’ to ‘The Republic of Cameroon’, the same name French Cameroon assumed at independence before federating with the British Southern Cameroons.

At 86, 2019 marks Biya 37 years in Power. He will be 92 when his current mandate ends in 2025 and more than 65 percent of Cameroonian youths were not born before he assumed office as Head of State.

Cameroon under Paul Biya has been accused of widespread corruption, embezzlement and dictatorship with the continuous silencing of political opponents, activists and journalists opposed to the regime. With allegations of indiscriminate killings, burning of villages, rape and humiliation of English-speaking citizens perpetrated by military forces, the nation is plagued with the Cameroon Anglophone crisis as former British Southern Cameroons continuously fight to secede to a state they name Ambazonia.

The State of Ambazonia

It is 58 years since both territories united, but the Anglophone minority regions have increasingly cried of marginalisation from the French majority. Anglophones say they have been decriminalized in education, law and administration by the dominant French government trying to ‘assimilate’ them as opposed to the terms and agreements of the Foumban conference in 1961.

The Anglophone crisis is the standing conflict and civil war raised by the Anglophone regions of Cameroon (former British Southern Cameroons) against the French-dominated regime.

In 2016, Anglophone Lawyers and teachers started a peaceful strike on the streets of major English cities like Buea and Bamenda. The protesters coordinated a sit-in strike demanding reforms in the legal and educational sectors but the Biya government reacted with harsh military actions, beating and teargassing unarmed civilians.

These strikes were initiated by the Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium (CACSC), a combined teachers and lawyers trade union. The following months witnessed a brutal clampdown by military forces on civilians.

By November 2016, at least 2 persons were killed and 100 protesters arrested and detained including CACSC leaders, Barrister Agbor Bala and Dr. Fontem Neba who led the strike.

Fast forward, this was the birth of the Anglophone crisis also known as the Ambazonia war. Other leaders who escaped arrest went on exile to countries like Nigeria and became vocal against the government. Spiraled attacks, wanton arrests, torture and killings led to the rise of an elite group of activists from the diaspora – with mission to establish the state of Ambazonia.

The federal state of Ambazonia (Amba Land) is the contested territory of former British Southern Cameroons, present two Anglophone regions. It is the nation separatists seek to establish in their fight against oppression and marginalisation from the government under Paul Biya.

The Ambazonia war is the fight to establish the federal state of Ambazonia. The war has been mainly between the Cameroon military forces and Ambazonia fighters (Amba fighters) who have picked up arms, imported sophisticated weapons and trained soldiers for war.

The scrimmage includes guerilla attacks, daily gun battles, shootings and mass killings in the Anglophone regions. Human rights groups have documented proofs of extrajudicial killings, mass burials, kidnap, arson attacks, arrest of civilians and the silencing of journalists from Cameroon.

War Zone

(September 8, 2019)

I was on a mission to report firsthand the hostilities in the Anglophone regions and paint an apt image of the ruined cities and war turned villages. My trip coincided with the days between the September 2019 twin lockdown announced by separatist fighters.

In these regions, separatists frequently imposed a lockdown (ghost town), a period of clampdown on all activities including businesses, offices, cars and movements of people.

During lockdowns, everyone stays indoors and the period records bloody battles and horrific killings. The separatist fighters are always up in battle against an Israeli-trained military.

The first announced lockdown was from 2 to 6 September, while the second operation was to take a break and run again from 9 to 13 September, 2019. We were in the break and it was a day to the start of the second lockdown.

I was ready to brave the gun-infested road from Buea to Kumba and Mamfe because I thought there was no better time to tell the sad stories of killings, arrest and war in these regions.

I touched down Buea landing at the Mile 17 park. The gentle morning breeze rushing down from the Buea mountain whispered through my ears as I watched a few clandestine vehicles queue up waiting for passengers. Standing around the park buildings were a few people whom I presumed were traders.

I could tell something was not okay. Usually, the park would boom from 6am when shops open, to about 2am the next day as people keep wake to chat over a beer, loud African music or sometimes watch football matches in clusters. But it was 8am, all shops remained bolted but for two traders selling to customers only from the window.

One of the shop owners tells me there was a serious gun battle that morning.

“There was an attack early this morning and I’m sure one of them was shot (referring to the military). Look that way, today may not be a very good day for business” he said, pointing to an uncompleted building with his mouth.

Towards the building, I counted about 6 military men, all armed and ready for battle. They stood firmly, each of them holding tight to the gun trigger as they patrolled. I could tell other colleagues were patrolling around.

In the Anglophone regions, it is normal to witness an attack but there was no guarantee you would live to tell the story.

Each time separatist fighters attacked or killed a military, inhabitants of the area were in trouble for military retaliation; they will either invade houses hoping to find the gunmen or mount unannounced identification searches that got several people arrested. Woe betide you if you were caught without an identification card.

My first major stop was Kumba so I hurried to secure a seat in an old Toyota Carina on the queue. We delayed at the park for over an hour with the driver hoping to have extra passengers before engaging the dreaded Kumba road.

I was already in the back of the car seated. They squeezed six of us in car meant to contain 3, and a fraction of my fellow passengers were young women. The driver charged double the usual fare, he said he was staking his life to transport us through the road.

It is approximately one hour fifteen minutes from Buea to Kumba. The 72 kilometer journey runs through other towns and villages like Muea, Ekona, Muyuka and Banga.

20 minutes after kickoff we arrived Ekona. Our car edged up the winding main road of what used to be a functioning village with lousy bar music and road trade.

Squat, tin-roofed houses gutted by fire, power lines strewn on overgrown verges and, above all, silence. Thousands of people used to live here but they were all gone, almost permanently living in the bushes.

In the silence, we drove pass the rusted shell of a burnt-out lorry by a shuttered bar. The buildings showed signs of war, holes ridden by gun bullets. I could spot some people peeping through the plank windows out of fear. Most of them were old people or women waiting to be gone if it was a military or separatist invasion.The men were already gone, they were the main targets of the war

Ekona has a history of numerous gun battles and records of dreaded killings. The town is a stronghold for several Ambazonia camps. In June 2018, a video surfaced on the internet showing military forces firing live bullets indiscriminately on the streets after separatist fighters blocked roads. I verified this video to be true passing through the actual spot of the shooting.

https://www.facebook.com/angie.forbin/videos/2139891272705796/

Three months after, an unarmed civilian was trying to change a punctured tyre of his breakdown car when he was shot by a military soldier who misjudged him thinking he was lying in ambush.

That same month, another man and his three sons were killed. Bezeng Jonas who was serving as secretary at the Presbyterian church Ekona was returning from the farm with his family. Inhabitants said they found corpses lying beside their vehicle.

The killings were numerous. Outbursts of gunfire were so frequent that children called them “frying popcorn.”

Another 8 people were shot by military forces in June 2019 and several others were injured.

“I personally saw over eight corpses, mostly men and a woman. They were lying in the bush. All of them were shot at close range,” a local resident who asked not to be named told Xinhua

There are always conflicting reports about the identity of persons killed in the crisis. Armed separatists claim that all those being shot by government forces are civilians and the army says they are separatists killed in counter-attack.

Government ministers have always fueled military killings. That the military is ‘defending territorial boundaries’, they are highly professional in protecting the land from terrorists.

Back in the car, everyone was silent. I could tell that the prayer was for us to snowball our way out of the warzone.

“Hmmm so this is what our nation has turned to? ” a lady seated at the front asked, presumably a way to spark a conversation but no one responded.

Several people had been arrested for throwing comments on the current political situation and everyone was on a red alert.

10 minutes after Ekona we arrive Muyuka, another town on the stretch of the road to Kumba.

Muyuka is the headquarters for sub villages and towns such as Owe, Ekata, Bafia, Muyenge, Yoke, Malende, Meanja and Mpundo. Just before reaching the town settlement we ran into an unusual checkpoint. Two military trucks packed on each side of the road and armed men in full combat gear, vigilantly scanning roadsides for any threats – their automatic rifles raised.

It was the BIR

The Rapid Intervention Brigade, BIR is an elite military force and an army combat unit of the Cameroonian armed forces. The unit is led by a retired Israeli officer and reports directly to Cameroon’s president, instead of to the ministry of defense. The unit has worked closely with the US military since 2007 or earlier, and is sent out only on special assignments to ‘crush’ enemies.

One of them flagged our car and walked closer for a routine check. He was a dark-skinned man, looking dreadful and armed to the teeth. With his combat boots firmly tied around his shin, his hand remained firmly on the rifle trigger which rested gently on his bullet proofed chest. His fingers were gloved and every part of his body covered but for his eyes shining from his combat helmet.

For two minutes he thoroughly examined the car without saying a word, from passenger to passenger and back as if he was expecting to see something new every time. None of us said a word. The military, I was made to understand, were under strict orders to ‘neutralize’ any suspect, even before double-checking.

Uneasily tensioned and frightened, it was one moment you would not wish your phone vibrated, talk less if I was recognized as a journalist conducting a report on the crisis.

The military had made it a routine to torture or imprison people after screening their smart phones to discover pictures, videos or messages relating to the Anglophone crisis.

‘Driver, open your boot and bring me your book’ the soldier said, moving to the back of the car.

Our driver reacted almost immediately. He joined the soldier at the back of the car with a pseudo smile. From the side mirror, I watched him squeeze money into the waiting hands of the military. It was a tradition to drop an “offering” each time you passed through a military control and all drivers had to comply – rather unwillingly.

Outside, on a military truck, a soldier stood holding tight to a Marksman sniper air rifle. His hands rested steadily on the trigger and his eyes were fixed on the riflescope as he stayed watch.

Muyuka

We drove into the settlement of Muyuka.

Just like Ekona, the crackdown here has been ruthless with residents experiencing frequent accounts of troops indiscriminately shooting or detaining civilians, and sometimes executing innocent young ones as they search for separatists who scurry away into the dense forest after attacks

In May 2019, a four-month old baby, Martha Neba was killed here. The family of the child accused soldiers of shooting the child on the head at point blank range.

“I quickly told my wife to run,” said Martha’s father, Funi Neba. “She went and hid around our neighbour’s house, I went right into the forest. On my way back I met a man who told me about the incident. I rushed home and saw my daughter on the chair. They damaged my daughter. I was seeing a bullet inside her head. You know how soft a baby’s head can be.” He told The Guardian

The height of the killings in Muyuka came in July 2018 when Father Alexander Sob Nougi was gunned down. Sob was the former Catholic Education Secretary and serving as the parish priest of Sacred Heart Church Bomaka, Diocese of Buea. Although early reports suggested the priest was hit in a crossfire between government troops and separatist rebels, Catholic authorities said Sob directly targeted.

Driving through the town, Muyuka’s thousands of residents had fled fighting between the army and separatist militias. The village was largely overgrown with a few people loitering around.

“It is weird. There used to be many more people here and it used to be busy. So this is what our country has turned to” another passenger broke the silence from our car.

“Hmmm you haven’t even witnessed anything yet” the driver responded as he explained what he called the most harrowing day of his life.

” In June 2019 I was on my way to Kumba with passengers when we caught in a gun battle. This one was heavy because it came from combined camps of Ekona and Muyuka. The shooting was in both villages and we were trapped in the middle. We spent more than 2 hours on the floor praying for gunshots to stop, everyone face-down on the road”

How did it end?” I poked him

“My brother we were finally escorted by the military. Two trucks rode with me on both sides of the road and they asked me to ride in the middle while they shielded my car from the bullets. I never believed we would make it out alive. So many passengers and drivers have been killed that way on this road. I want to stop the work but how can I leave when I have a family of seven to feed every day? “

He was right. 14 days into June 2019, dead bodies were discovered at an advanced stage of decomposition in Ekona.

After Muyuka, we made a ride through other smaller villages which were also deserted. The common thing about them all, were remnants of battle. They either had houses with holes ridden by gun bullets or skeletons of vehicles set ablaze by the side of the road.

Around a bend, we ran into another checkpoint. This time it was the Ambazonia fighters.

Four armed men in civilian clothes, all black, with traditional necklaces and other things that looked like amulets. One of them had a bandolier slung sash-style over his shoulder, he had ammunition pockets across the midriff and chest.

He was just about finishing with another car when we arrived. He flagged our car and told us to contribute to their course.

“Drop something to support us, we are fighting for your freedom, Ambazonia must be free” he said.

“Quick quick” another implored us to hurry. We finished the formality and drove off. I could tell there were many other fighters settled in the bush.

K Town

15 minutes later we were in Kumba. The entire journey had taken us about an hour because there was no usual traffic and our driver rode on extreme speed.

Kumba, a metropolitan city, is capital of Meme division in the Southwest Region. It is popularly referred to as K Town and is the most developed, and largest city Meme attracting neighbouring villages like Mbonge and Ekondo Titi.

The town has an estimated population of about 400.000 people. Just like any other Anglophone city, K Town equally recorded news of several wars, kidnappings and deaths originating from there.

In February, at least three corpses were discovered around the Kumba II council Business Center in Kosala, with blood from bullet wounds.

Cameroon celebrates every February 11 as Youth Day but separatists identify it as the day their English-speaking territory was handed to the French-speaking majority who now maltreat them. It is the day the British Southern Cameroons voted to join the Republic of Cameroon. For the past three years, the day always witnessed a lockdown to puncture all government activities and celebrations.

This year February 11, four persons were consumed in a fire that raised down the Kumba district hospital. The fire swept through the male and female surgical wards, the maternity ward, the nurses’ quarters and consumed five cars. The four who died were all patients, burnt alive.

The government said attackers were mainly from the Ambazonia separatist movements while the Ambazonia government which largely exists in exile, also published a press release accusing government officials of burning down the hospital and placing the blame on the separatist fighters to win the sympathy of locals and gain international support.

Later in May 2019, the corpse of Meboka, a popular motorcycle rider was discovered lying on the streets. Meboka was reportedly killed because soldiers suspected him to be an informant of separatist fighters in the locality.

Abandoned corpses became a recurrent theme as fighting regularly erupted between security forces and separatist fighters. But the government’s near-total lack of prosecutions for crimes by security forces and failure to dialogue with separatists has protected fueled abuses. No one claims responsibility for killings and no one gets punished.

From Buea road, I boarded a bike to the Mamfe park, taking a drive through the city.

Though K Town always recorded cases of extrajudicial killings and attacks, it appeared the inhabitants had become used to the war. The town was seemingly scanty but live had not vanished completely.

An inhabitant told me they have become used to ‘frying popcorn’. Frying popcorn is a word used to describe the sound of constant gunshots. “Sometimes we hear sudden gunshots for about an hour and minutes later someone drops dead, we mourn and bury. But hours later, everyone gets back to their business else we would all die of hunger “.

That week alone, at least four suspected separatist fighters were killed.

Traffic controls, a brief ride round the town and other travel delays, by 2pm I took off from the Mabanda park in Kumba, headed to Mamfe.

Brush With Death

From Kumba, it takes 2 hours, 30 minutes to Mamfe. The two towns are separated by several villages and towns which are in no way an exemption of the sad effects of the crisis. Some of these villages and towns are worst hit by the crisis as they have become major settlements and camps for separatist fighters, and a constant point of attack for the military.

Again, six of us got squeezed into a car meant for three persons. Before we left, our driver began receiving advice against engaging the road. He was told there had been skirmishes.

Five years ago, the Kumba-Mamfe road was a nightmare for travellers. We would have spent an entire day pulling the car through mud with numerous breakdowns.

The road is only 149 km and cuts across the second largest cocoa-growing area in Cameroon. It is a natural extension of the Bamenda-Enugu(Nigeria) corridor and a very important segment in the Lagos-Mombasa Trans-African Highway. It could also be very lofty and vibrant in the much talked about trans-African freeway vision.

30 minutes into the journey, some kilometres before Ikiliwindi checkpoint, we met a corpse lying on the road. Blood oozed from it running into the culverts as the driver warbled through.

Fear gripped our hearts, it was evident that we had walked into a deadly zone.

Between Konye and Super, the village preceding the overpass, we met an unusual checkpoint. “Oh not again! ” a passenger lamented.

Arrmed men, all civilians with guns and red pieces of cloth tied over their muscles. They asked us to again contribute to the struggle.

They asked that we step out of the car to drop the donations on the ground. One of them called me in a familiar tone. Surprised and scared I looked at him waiting to hear my bad news. “It had finally come to my turn” I quickly to thought myself.

“Arreyb, brother I recognize you, yes it’s you the journalist”, he said showing me my way back into the car as we kicked off. I breathe a sigh of relief. For the first time, I felt I was so close to death.

Three weeks before this journey, I was in London where I reported live from the BBC headquarters on the life sentence of the Ambazonia separatist leaders.

Just before Konye, there was a military checkpoint. More than three vehicles whose passengers used the stop as an opportunity to take a break.

Just there, we were caught in a crossfire as separatist fighters attacked. A group of men shooting desperately at the military. Amidst deafening gunshots, all of us slept on the ground. Other terrified passengers began running as guns echoed all through the terrain …

Up against the professional military forces were a group of Amba fighters who ambushed from the nearby bush. Each time they fired shots, I heared them shout “Water na Water”, a phrase they used to describe their immunity to bullets.

We stayed down for over thirty minutes. We tried to move each time the place seemed silent but shots were fired from another end as if the whole process was about to start a fresh.

In 2017 when the gun battles began, one could differentiate the sounds of military rifles and pellet guns (hunting guns) used by separatists. But this time both shots sounded the same. Separatists had definitely upgraded to AK 47s and rifles, just like the military.

Just then I saw two officers with riffles escorting a dark-skinned young man. His hands were cuffed and they pulled him mercilessly.

I believe I saw Peter (not his real name) walk to his death. He was being escorted to the ‘stake’ by armed BIR soldiers. They said he was one of the attackers. Sadly, he could not see his mourners and sympathisers watch his final walk because he was blind-folded with a piece of black cloth. They led him towards a tree by the side of the road and I read gloom on the faces of other passengers. I guess their guess was my guess.

The driver told me such cases of attack were frequent and the BIR may deal with him at the moment for the many passengers transiting the checkpoint to be eye witnesses and to serve as a deterrent warning to other young men.

Its was getting late and the following day was to be a lockdown, so we left for the rest of our journey. Just before Batchuo Akagbe, we came across another military checkpoint. They performed their routinely identification check and we drove on.

Surprisingly, just 200 metres ahead we were flagged by a separatist group.

“And they operate this close?” a fellow passenger wondered.

“In some areas, it looked like they have come to an understanding to respect each other’s lane until when there is a combat” responded another.

We spent the rest of our journey in silence. In the fear and looming danger, everyone was hoping we snowball our way into Mamfe before night fall.

Far From Dialogue

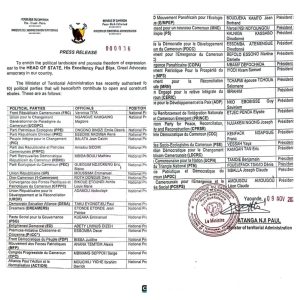

Since 2016, all prospects for peace talks and dialogue between separatist fighters and government authorities have failed. Separatist fighters took up arms when government reaction to the crackdown was a military invasion, torture and detention of leaders in 2017.

Though the government has severally said they are willing to dialogue, no action has been taken to convene the struggle leaders and government authorities on one table.

At the start of the struggle, striking lawyers and teachers simply wanted reforms for the English speaking regions. These reforms gradually developed into a movement for a return to the abandoned federal system – to let each region manage and control their resources, elect their governors and report to a central state authority.

In the same period, members of CACSC were arrested and others brutalised. Some fled the country and metamorphosed from federalists to separatists – to support the complete separation of the Anglophone regions from Cameroon to the state of Ambazonia

Federalism lost support among Anglophones with the rise of diaspora based activists like Mark Bareta and Tapang Ivo who led CACSC at the time.

In May 2019, the Biya regime announced it was ready to discuss with ‘rebels’ but said they would not consider the option of secession. Separatists have said they will never accept.

They insist that any talks must be led by a neutral party and possibly held out of Cameroon for the safety of diaspora activists, after the regime releases all those incarcerated in military prisons as a result of the war and demilitarizes the Anglophone regions

With no sign of peace, the regions continue to experience bombings, attacks, extrajudicial killings, arsons and daily gun battles. Civilians find themselves in the middle of the insurgency and at least on person is killed everyday. Paul Biya’s close cooperation with western states has made the crisis slip beneath the international radar.

Since 2017, we have staked our lives to provide tailor-made news reports to our readers from war zones and hot political rivalries in Cameroon - And we do so for FREE.

As a small online media now reaching over 100,000 monthly readers on all our platforms, we have to rely on hiring a small team to help keep you informed

The best way to support our online reporting is by considering a measly sum for our team on the ground as little as $1. Now you can make a donation to us below, it only takes one click...

[sdonations]1[/sdonations]