By AKERE T. MUNA

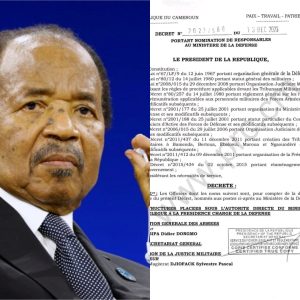

On 6 November, Paul Biya was inaugurated for the seventh time. The 85-year-old has already been in power for the last 36 years and will now serve another seven-year term.

He was re-elected in heavily disputed elections on 7 October amidst rising unrest. Cameroon is divided into the Francophone area – which makes up four-fifths of territory – and the smaller Anglophone area. In the last two years, the latter region has been in a situation just short of civil war.

Over the decades since unification, the Anglophone regions have been increasingly dominated and felt resentful. This escalated into a movement that, in 2016, held strikes and peaceful demonstrations. Activists called for the restoration of the English-speaking education and judicial system.

The government, however, responded with furious repression. It shut down any discussions about federalism. This led to a spiralling crisis.

Today, the talk is about secession and the conflict has become bloody. There are now over 300,000 internally displaced persons and more than 40,000 refugees in Nigeria. At least 90 villages have been razed, while over 400 civilians have been killed and thousands more wounded. 40% of Cameroon’s revenue derives from the Anglophone regions, but the local economy has been deeply undermined by insecurity.

For the president by the president

This is the context in which Cameroon’s elections were held last month. In theory, this exercise is an opportunity for citizens to shape the direction of the nation. But the reality is very different.

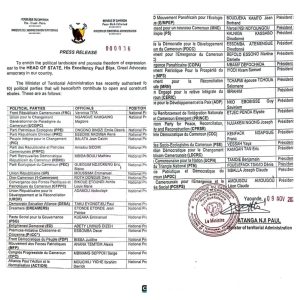

The body that organises Cameroon’s elections is supposedly autonomous, but all its members are appointed by the president and can be removed at will. All electoral disputes are settled by the Constitutional Council, but all its members are also appointed by the president. The Minister of Territorial Administration, another presidential appointee, handles all other administrative issues connected with the process.

Cameroon’s first-past-the-post system also privileges the incumbent. Meanwhile, the use of multiple ballots –whereby voters are given papers for all the candidates and then cast their vote by putting their favoured nominee into the ballot box – allows vote-buyers an easy way to check how people voted. Calls to adopt a single ballot paper system have been ignored.

The barriers to challenging the president in the first place are also steep. Nominees must pay around $60,000 to submit their candidacies. They must either be endorsed by a party with at least one elected official or, if running as an independent, produce at least 300 signatures from specific kinds of dignitaries from every region.

In the elections themselves, there are close to 25,000 polling stations. What candidate can field representatives in each of these locations? The official campaign period lasts two weeks and it is illegal to campaign before this period. How can one visit 360 districts in just 14 days? The presidential campaign team, which includes ministers and other high-powered officials, travels the country at the expense of the state, meaning the playing field is nowhere near level. Meanwhile, the state media turns into the ruling party’s propaganda machine.

Why I ran

Despite all these very high hurdles, I decided to run for president this year. I have spent the last 25 years defending good governance and fighting corruption. In 2000, at a time Cameroon was accused of being the most corrupt country in the world, I founded the national chapter of international anti-corruption NGO Transparency International. Needless to say, this earned me the ire of the establishment. I went on to work for bodies such as the African Development Bank and High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa.

In this time, I watched as my country steadily moved in the wrong direction. And with the worsening situation in the Anglophone regions threatening to pull apart the fabric of our nation, a sense of responsibility weighed on my soul. I knew that I had to put my experience at the service of our citizens and attack the issues at their source – the system.

I submitted my candidacy, though in the end I withdrew and backed Maurice Kamto. There is nowhere in Africa where the opposition has removed a dictator like Biya without presenting a common front. I therefore called on my supporters to get behind a fellow opposition leader, but while the remaining eight candidates held some further meetings, they did not meet once together as a group. This meant that there was no single opposition candidate to challenge President Biya.

This fact discouraged many voters who concluded the process was a waste of time and the result a foregone conclusion. Turnout fell from previous elections to just 54% and was as low as 10% in the restive Anglophone regions.

The system or the streets

In the final tally, Biya officially won with 71.28%. Kamto came second with 14.23%. But there were reports of massive fraud. The absence of opposition officials at many polling stations allowed the stuffing of ballot boxes. An incomplete biometric system meant that some people voted multiple times.

The legal challenge against the election results that followed exposed the Constitutional Council as a political institution. This all played out on national television and many citizens, for the first time, witnessed the fraud that cripples our electoral process.

The danger that Cameroon now faces is that its elections’ lack of credibility could lead voters to question the need to participate at all. And if electoral justice becomes captured by politics and hence incapable of addressing issues raised through the proper avenues, the streets will take over. Since the elections, there have been demonstrations against what has been described as a deeply faulty process. These demonstrations have been relayed to the diaspora in Europe and America.

Amongst other things, Cameroon needs to design an adequate electoral system. It is essential to make reforms so that the individual controlling the process is not also a player in it. This will of course mean the incumbent’s huge advantages are reduced, but if the electoral playing field is not evened out then the country risks being stuck in an interminable loop created by a government for the government. And Cameroonians will only stand for this so long.

Till then, Cameroon sadly remains a state captured by a few oligarchs.

Since 2017, we have staked our lives to provide tailor-made news reports to our readers from war zones and hot political rivalries in Cameroon - And we do so for FREE.

As a small online media now reaching over 100,000 monthly readers on all our platforms, we have to rely on hiring a small team to help keep you informed

The best way to support our online reporting is by considering a measly sum for our team on the ground as little as $1. Now you can make a donation to us below, it only takes one click...

[sdonations]1[/sdonations]